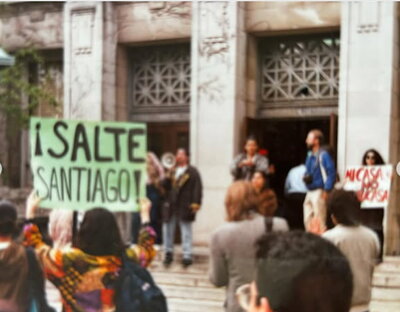

On May 5, 1992, a diverse coalition of more than 450 people, mostly students, gathered in and around the U of I’s Henry Administration Building with the goal of increasing institutional support for Latina/o students and programs on campus. Their demonstration followed a smaller, unsuccessful sit-in at the Office of Minority Student Affairs on April 29.

The students’ demands called for the creation of a Latina/Latino studies program, hiring additional Latina/o faculty, staff, and administrators, increasing funding and support for the cultural center La Casa Cultural Latina, and increasing recruitment and retention efforts for Latina/Latino students. They also called for the elimination of Chief Illiniwek and for the university to also support Indigenous students, many of whom also have Latina/o heritage.

In response to the students’ demands, Chancellor Morton Weir appointed a committee of three faculty members, the Palencia-Roth committee, to investigate the problem. According to the Daily Illini, the committee’s report, submitted on May 8, 1992, said “university support for the Latino community had been token.”

After a peaceful sit-in that lasted several hours, students were ordered to leave the Henry Administration Building by university administrators. According to The Chicago Tribune and a video documentary of the event by Richard Freeman, after students refused, police dressed in riot gear forcibly removed students from the building and some left voluntarily. Protesters reported injuries from stun guns and billy clubs. 60 letters of reprimand were issued to students who participated in the protest and three students were arrested on charges of resisting a police officer.

After the protests, the Illinois General Assembly passed a resolution sponsored by Senators Miguel de Valle and Alice Palmer requiring an investigation into the problems concerning Latina/o students at the U of I. According to the resolution, the university was asked to conduct an inquiry and submit its results by August 30, 1992.

On June 30, 1992 the university announced that it would begin developing a Latina/Latino studies program, locate a different building for La Casa Cultural Latina, and begin recruiting additional Latina/o administrators, faculty and Latina/o students.

This wasn’t the first-time students, faculty, and staff organized for a Latina/Latino studies program. In the 1970s, a group of student organizations, faculty, and staff advocated for a Latina/Latino studies program, starting a cultural center, and hiring more Latina/o faculty and staff. Their activism led to the founding of the cultural center La Casa Cultural Latina, which develops educational, cultural, socio-political, and social programs for Latina/o students. La Casa Cultural Latina, which recently celebrated its 50th anniversary, and its newsletter, La Carta Informativa, were a key hub for the student organizers of the 1992 protests.

Multiple committees were formed between the fall of 1992 and spring of 1995 with little movement on the issues, though the university did begin to recruit Latina/o faculty, and La Casa Cultural Latina was moved to the building it occupies today at 1203 W Nevada.

Alicia P. Rodriguez (MA, ‘91; PhD, ‘96; educational policy studies), a graduate student who was active in the ‘92 movement with the groups La Fuerza and a feminist group with the University YWCA, was hired as a graduate research assistant back then by anthropology and Latin American and Caribbean studies professor Enrique Mayer to help the university research other Latina/Latino studies programs around the country and explore the possibilities for a program at Illinois. Programs existed in California and the Southwest that were focused on Mexican-American/Chicano studies, but organizers wanted the program to reflect the diverse Latina/o populations in the Midwest.

“We were really cognizant of that and trying to realize that whatever the program would be like here is not necessarily going to be the same as you would see elsewhere in the country,” Rodriguez said.

Many students who were involved in the ‘92 protests graduated or left the University. The next class of students took up the fight however and continued to put pressure on the administration to create a program.

“The students were super active and they were working with not only Latino faculty but other supporters of the initiative within the university to really make it a program that was the right thing for the university and was attending to the students’ concerns,” said Rodriguez.

Finally, by the fall of 1996, the program of Latina/Latino studies was established along with an interdisciplinary minor in Latina/Latino studies. Professor Rolando J. Romero was appointed as the first director. In 2003, Rodriguez was recruited to join the program as an associate director. The program hired its first tenure-track faculty member in 2002 with joint appointments in communication (now media and cinema studies), history, and sociology. In 2007, the program tenured its first jointly-appointed faculty member with the Department of English. By 2008, the program had three faculty members with full appointments in Latina/Latino studies, nine faculty members with partial appointments, and sixteen affiliate faculty members.

Though students couldn’t graduate with a degree in Latina/Latino studies, they could complete an individualized plan of study degree. By 2008, nine students had graduated with individualized plans of study degrees in Latina/Latino studies.

In 2007, Isabel Molina-Guzmán (currently the LAS associate dean of student academic affairs), became interim director while program director Arlene Torres was on sabbatical. She and Rodriguez worked together to lead the department through the detailed processes and proposals required to become a department, building on the groundwork laid by Torres.

To become a department, units must have a major and be able to tenure and hire faculty. The program also developed a graduate minor. The program and major had to complete approval processes with the college, academic senate, and Illinois Board of Higher Education. In October 2010, the Illinois Board of Higher Education approved the establishment of the Department of Latina/Latino Studies and the major. Molina-Guzmán then became the first chair of the department and Rodriguez became the academic advisor and administrative coordinator. In the spring of 2011, students could officially begin to major in Latina/Latino studies.

“Really the impetus for becoming a department came from the student protest of the 90s,” Molina-Guzmán said. “They wanted more Latino faculty and they wanted Latino studies taught at this campus. And so we became the very first Latina/Latino studies department in the country.”

The movement to create a department at Illinois fostered a generation of Latina/Latino studies scholars, including Latina/Latino studies professor Mirelsie Velázquez.

“The people that were fighting for the institutionalization of the department became leaders in the field because of the work they started as undergrads here. I have a list of 10 of us that are now Latina/Latino/Latinx faculty across the country,” said Velázquez. “There’s a really big genealogy that is accredited to this space. Not the institution, but specifically this department.”

From left to right: professor José A. de la Garza Valenzuela, professor Nic Flores, professor Mirelsie Velázquez, office manager Marisol Hughes, chair and professor Gilberto Rosas, professor Elizabeth Velásquez Estrada, associate chair and professor Natalie Lira, professor Janett Barragán Miranda, academic program coordinator Sean Ettinger. Not pictured: professor Aja Y. Martinez, lecturer Randy Rodriguez, and communications coordinator Heather Gernenz.

Velázquez is working on a book, tentatively titled Genealogies of Empowerment and the Makings of Home: Latina/Latino Student Activism at the University of Illinois from 1970 to 1992 that collects oral histories from people involved in the movement. She said that Latinas’ contributions are often left out of the history of the movement and hopes to rectify that in her book.

“There's a lot of gaps in the archives. And if we don't start collecting our own community histories they’re going to be lost,” she said. “The book is really just a big thank you in so many different ways and a way of making sure that future generations, when they're dealing with the same kind of questions, have a road map on how to engage with one another.”

Today the Department of Latina/Latino studies is one of the nation’s exemplary interdisciplinary departments exploring the Latina/o experience from a sociological, historical, and cultural perspective. In 2026, it will celebrate its 30th anniversary. The department has nine award-winning faculty members and fifteen affiliates who are consistently ranked as outstanding teachers by their students. Through their coursework, LLS students become empowered to think critically, solve problems, and understand topics related to power, privilege, inequality, and social justice.

“I think the ethos of Latino studies has always been to create a space where students felt and feel themselves seen in the curriculum and seen by the faculty and staff,” Molina-Guzmán said. “So we're still a relatively young department and still growing, you know, still finding our footing. But I think in terms of the core mission of the department, we're still what we were like as a program. We're home for faculty all throughout campus and provide that space that undergrads always wanted to have for themselves and to see themselves reflected in the curriculum and the content of courses and research.”

Recently retired, Rodriguez served the department for over 20 years and was active in curriculum planning and mentored hundreds of students. She said her background as a student activist informed her work and advocacy for LLS students.

“Having that knowledge allowed me to understand what the program could be and what it should be and I was always making sure that students were at the center of it all. And not forgetting that it was a student movement that brought this about. It was their vision, their wisdom about how the university needed to address and should address Latino issues that was central. So for me, throughout the time I was working in LLS, I was always very student centered and always very aware of the importance of putting students in positions of power where their needs are addressed and the program serves them,” she said.

Latina/Latino studies graduates are innovators and leaders in a wide range of fields, such as applied health, law, journalism, social work, English, education, activism, arts education, government, and business. Illinois State Senator Celina Villanueva and Teresa Ramos, first secretary of the Illinois Department of Early Childhood are among the ranks of LLS alumni.

“I think the students have just risen to the top in terms of their intellectual fervor and their intellectual accomplishments. And not only their academic accomplishments, but also their social accomplishments and civic accomplishments. Students are learning about issues that are relevant to important topics of the day and they are able to translate that into action and ways to improve society by addressing Latino concerns, Latino issues and problems,” said Rodriguez.

The department’s history is not forgotten. LLS students learn about the history of the department in LLS 100: Intro to Latina/Latino studies and LLS 238: Latina/o Social Movements. When Velázquez teaches LLS 238, she gives students a copy of the 1992 list of demands and asks them to create their own. Concerns about recruitment, retention, institutional support, and a lack of Latina/o faculty in other units remain high on the list.

“It’s the exact same list of demands or at least concerns that they have about their time here. My hope is that at some point, we don't just listen but we react to what they're saying,” she said.

Editor's Note: A shorter version of this story was originally published in the May 2025 issue of the College of LAS Quadrangle.